by Amber Mann Riggs

“It seems like we are speaking two different languages.”

If you have ever thought this, you aren’t alone. As religion columnist Phyllis Tickle observed, approximately every 500 years, Western culture—and the Church in particular—undergoes such a significant change in paradigms that words often develop two sets of meanings. True to the pattern, we are currently in an era of significant transformation.¹

Anyone who spends much time reading serious analysis of 21st century Christianity, culture, and ministry is going to come across the term “postmodernity”. Indeed, much of our understanding of culture is directly dependent on our ability to understand postmodernity.

Yet, for all its significance, it is often a weighted word thrown around with the assumption that the person reading it understands the dimensions of its weight.

In the parts 1 and 2 of this series, we explored postmodernity’s parent philosophy—modernity—and how it impacted Christianity.

In part 3, we’ll see how postmodernity grew out of and reacted to modernity, leaning heavily on insights from historical theologian Dr. Robert Webber.

A Review of Modernity

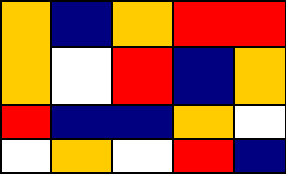

Let’s take another look at our graphic representation of modernism. Each block is unique and primary. Each block is its own entity, and yet it makes up the whole. Likewise, when we look at the whole, our eyes are drawn to individual blocks of color. The colors in the graphic representation are the primary colors: yellow, blue, and red. These colors are the foundation for every other color that there is.

There is also an absoluteness about the blocks. It is very clear where one block ends and another begins. They are characterized by linearity. Straight lines form perfect rectangles that can be measured and described in absolute terms. Because modernity is individualistic, linear, and rational, modernity allows for the world to be defined in absolute, quantitative ways. It is simple, clean, and mechanistic.

The modern worldview was largely a response to the Enlightenment. The world was experiencing great changes, so culture adopted a new paradigm through which they could interact with the world. Scientific discoveries, breakthroughs in communication, and many other technological advancements engendered an individualistic, rationalistic culture. With modernity people viewed the world as a machine. Each part of the world was definable and had its own role. There is a precision about modernity. Knowledge is clear and attainable. Facts are unquestioned. There is absolute truth, and that absolute truth can be discovered.

So what happened? Although modernity and postmodernity appear to be opposites in many ways, modernity essentially gave birth to postmodernity. Modernity is responsible for shaping postmodernity. Modernity was characterized by the notion of progress…and that very progress caused people to question the values that made the progress possible. Modernity revealed so much about the world that it ironically determined that the world is so complex that everything about it cannot possibly be discovered!

An Introduction to Postmodernity

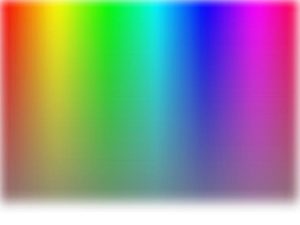

Whereas we compared modernity to primary colors, postmodernity is the whole color spectrum. We don’t see individual pixels or blocks…we see a whole. And that whole can’t be described easily. It’s still made up of the same colors, but we find it more difficult to describe this in terms of simple reds, yellows, and blues.

Pick a color pixel in the blurred area in between yellow and green. Is it yellow, or is it green? Can it be both? If we put it next to a yellow pixel, it would appear green, but if we put it next to a green, it would appear yellow. What color is it really? Yellow and green are definable and yet…relative.

Think about this in terms of ethnic heritage. It would not be considered strange today for someone to cite their heritage as being White, Black, Latino, and Asian. Do they have to be only one? 20 years ago, the answer to that question would have been yes. Likewise, mixed heritages were once looked down upon because of those strict ethnic lines. However, there is a movement today to allow people to check more than one ethnicity box. Individuals with more than one heritage are recognized as being uniquely beautiful.

The above graphic representation is fluid and lacks linearity. Although the full spectrum of color is present, it hints at mystery more than absoluteness. The colors are in community with one another. Red interacting with yellow at a variety of different levels. Yellow interacting with blue. Blue interacting with red. All three of them interacting with one another.

What’s your favorite color? Green, you might say. But not pea green, not grass green, not emerald. But a mossy green. Postmodernity recognizes the spectrum of colors and gives you as many choices as it can.

The Scientific Revolution

Inevitably, as modern scientists continued to discover truths about the world, more changes began to take place. Modern science had at its foundation the atom. Atoms were “the building blocks of life.” And then the atom was smashed. There is something smaller than the atom?! The building blocks were essentially shattered. And in that shattering a great source of energy was found. It revolutionized science.

The modern world was a world that stood still. We could, for example, capture snapshots of the modern world and then use those snapshots to make generalizations about the world. The postmodern world, however, does not stand still.

Complexity and Uncertainty

As more and more discoveries are made, there is more of a realization that things don’t take place in isolation from one another. Instead, there is this constant interaction between systems. Consider the ecosystem: we have animals, vegetation, natural resources, and humans sharing the world. Each plays a key role in our environment. It’s amazing the impact that moving one species into a new environment (in order to help the functioning of that environment) can cause major problems in the new environment! The idea may have worked on paper, but the interactions prove differently. Thus, we continue to develop more and more complex systems for understanding our world, and we realize more and more that there are no simple answers.

The postmodern world is a complex world. Modern scientific discoveries brought us back to the mysterious world that modernity had left behind. It’s the world of the Heisenberg Uncertainly Principle, which states that we never know both the exact position and the exact speed of an object. We can only know one or the other.

Interpreted Facts

Are there still facts that we can know about the world? Yes and no. Webber notes, “Because matter is in perpetual movement, postmodernists argue that we cannot arrive at rational and scientific facts. So-called facts are only interpreted facts. Therefore, it is now recognized, even in science, that one needs to bring to “fact” a framework of thought that is based on faith. The assumption that there is no God is a faith commitment as much as the assumption that there is a God.”²

The impact of science? A return to a realization of mystery and complexity within the world; a recognition that everything in the world is interrelated and dynamic rather than static; Facts can no longer be looked at objectively but can only be interpreted based on our prior knowledge and beliefs about the world.

The Philosophical Revolution

Modernity was characterized by “I think; therefore, I am.” We can see how that statement went hand in hand with the modern scientific view. However, we also have to ask how the change in science impacted philosophy…

Webber notes 4 major changes:

1. Life as the interaction of all things.

Modernity held that you could study an object and, looking at that object objectively, come to absolute, unbiased conclusions about that object. Potential emotional interactions with the object were denied. For example, you were expected the study the Bible and come to conclusions about it without involving your emotions. Emotional involvement was seen as distortion and tainting of facts. Postmodern philosophy, however, validates the idea of subjectivity. That is, the interaction that inevitably takes place between two entities or individuals. Recognition that the world is “interrelated and dynamic rather than static”.

Whereas modern thought caused us to look at the Bible objectively, postmodern thought encourages us to put ourselves in the Bible story. To put ourselves in the shoes of the woman at the well and try to understand the scope of the impact that Jesus had on her instead of focusing primarily on the theology of that which was spoken. In lieu of viewing the world as individuals separate from one another and from the objects which we study, postmodern philosophy encourages us to view life in terms of the interrelationship that comes in community. Thus, we see a shift from individual to community.

2. Everything is relative to everything else.

Because we are in relationship with our environment, we are in a continual interaction with our environment. The precise truth about an object may not still be true 1 minute from now. For example, if I were to describe my dog right now, I would use the words lazy and lethargic. However, I don’t know that a squirrel won’t get his attention in the next minute by jumping off the roof and therefore causing my dog to become alert and animated. While individual snapshots of my dog hint at his character, he is continually interacting with his environment.

Another example would be to look at post-traumatic stress disorder. As a student attending college in Denver, I had the opportunity to interact with a group of students who had been students at Columbine High School at the time of the shooting. Over two years after the incident, one of the students, who had actually been friends with the two killers, shared how he had come to avoid looking at digital clocks during certain times of the day simply because numbers (such as 4:20) that had previously been meaningless to him now caused him to be overwhelmed with emotion. Loud noises that resemble the firing of bullets still caused him to experience bursts of panic and anxiety. These are a few examples of how things take on new meaning as a result of ongoing life experiences.

3. Pluralism.

Science cannot point to one “unifying factor to the universe.”³ There is no scientific “key that opens the door to the universe.”4 Instead, it is a web of things in relationship with one another that causes the universe to function as it does. Pluralism (note the word plural) acknowledges many factors at work as opposed to one unifying factor. Of course, as Christians we see that God’s creative Word is the unifying factor. But within science, there is such a diversity of factors at work that these factors create a complex, mysterious system. And quite fittingly, since God is both complex and mysterious.

4. Language cannot present the fullness of truth.

Truth is indescribable and can only be fully understood in its original context. In modernity, each word has a precise meaning, but postmodernity states that words present only a shadow of the truth. That is, words can only point to the truth. Language through the eyes of postmodernity “reflects social constructs pertinent to particular social and historical contexts.”5 In other words, we can read the words, but unless we put ourselves in the original context in which they were spoken, we cannot grasp the full power of the words.

Let’s look at how this impacts the idea of one universal metanarrative. Modernity acknowledges that each community has its own metanarrative, but that only one metanarrative can be “right”. Postmodernity, however, recognizes the role that a community’s own metanarrative plays in understanding that particular community. It is the difference between looking at the history of Native Americans from the Native American’s perspective and the European American’s perspective. History looks differently depending upon whose eyes we are using to analyze it.

The problem arises when we apply the validity of many different metanarratives to religion. All of a sudden, there is an apprehension regarding understanding the world in the context of something that happened 2000 years ago in a culture very different form our own. There is a reluctance in accepting the Judeo-Christian metanarrative as a framework to understanding the world. This has resulted in an “every religion leads to God” type of philosophy. Muslims come to God through Mohammed, Hindus through Brahman, and Buddhists through nirvana. Yet, there is the belief that each of these religions can bring people into contact with the same deity.

The Communications Revolution

Think about some of the ways that communication has changed over the past 100 years. It has been huge! We now have not only telephones but smart cell phones. We’ve gone from newspaper to radio to television to the internet. From records to 8 tracks to cassette tapes to cd’s to mp3’s. We don’t just have music – we have music videos. And as the music plays, music videos tell a visual story that often enriches the original song. We communicate not only in words, but in symbol. And these symbols are powerful communicators.

We can take a concept and write about it…but when we put it into poetry, the meaning often becomes deeper. Add music to that poetry and the message becomes even more powerful. However, if we add a visual aspect, we can become involved with the words on an entirely different level altogether. We have begun interacting with the words and the ideas behind the song. We participate with emotional attachment.

Webber writes, “The new postmodern shape of communications has shifted to a more symbolic form. It is knowledge gained through personal participation in a community.”6 The emphasis has shifted from logic and reason to intuition and experience.

A Comparison

Webber makes the following comparisons between the modern worldview and the postmodern worldview on page 37 of Ancient-Future Faith.

| Modern Worldview | Postmodern Worldview |

| The Scientific Revolution | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The Philosophical Revolution | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The Communication Revolution | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

To sum up the postmodern paradigm: The world is a mysterious world that is to be experienced. Not objectively, but subjectively as we interact with the world. We live not as individuals but as a community. We communicate not through precise words but through a symbolic canvas of sounds, colors, smells, and touch that make communication an experience.

In the final article of this series, we’ll explore specific ways that postmodernity has impacted Christianity.

Notes:

¹ Phyllis Tickle, The Great Emergence (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books. 2008).

² R. E. Webber, Ancient-Future Faith (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic. 1999), page 21.

³ Ibid., p. 23.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid., p. 24.

6 Ibid., p. 24.